The route tracking An–ski's ethnography and journalism

We invite you to a journey in the steps of a Jewish ethnographer, writer, and social activist – S. An–ski.

The route includes 7 townships in Volhynia: Luboml – Volodymyr-Volynsky – Kovel – Lutsk – Ostroh – Dubno – Kremenets – Korets.

The route: 420 km, time of a car journey – one week.

Visiting the townships along the route is connected to the topics present in the source materials (reports and folklore) and the preserved iconographic materials.

An-ski was born in 1863 in Czaśniki in the Vitebsk Governorate as Szlojme Zajnwił Rapoport. He was brought up in a religious Hassidic environment and received a traditional religious education. When he was 16 he broke away from the tradition and got connected to the Narodniks movement. In 1887 he received a Russian name and patronymic – Siemion (Szymon) Akimowicz – and worked as a miner in the Donbass (Yekaterinoslav Governorate). He was deeply engaged in the issues of workers, he wrote numerous documentary texts and sent them to Russian newspapers.

After one of the editors recommended him to a Narodnik writer from Petersburg – Gleb Uspienski – Szymon Akimowicz came to Petersburg in 1891 and started to write for the "Russkoe Bogatsvo" newspaper. It was then that he decided on his nom de plume – S. An–sky.

In connection to his anti-Tzar activities, he had to leave Russia and was in emigration between 1892–1905. He served as a secretary to writer Piotr Pawłow, after whose death he settled in Geneva, where with Chaim Żytłowski and Wiktor Czernow he founded the Russian Social Revolutionary, which then became a part of the Socialist Revolutionary Party.

At that time An–ski had a fascination with the works of Isaac Leib Peretz and started to write in his language himself.

He returned to Russia in 1905. He took part in the works of the Jewish Society for History and Ethnography, the Jewish Literary Society, and worked with the newspapers: "Evreiskii Mir", "Evreiskaia Starina" and "Perezhitoe". Jewish themes started to play an increasingly significant role in his writings. At that time he also took interest in ethnography.

The Expedition (1912–1914)

In 1909 An–ski came up with an initiative for a scientific event – an ethnographic expedition to the "Pale of Settlement" area. The aim of the expedition was to research the traditional culture of Eastern–European Jews. An–ski was of opinion that archaic motifs present in it will soon be destroyed because shtetls are increasingly more prone to "external" cultural influences. It is worth mentioning that An–ski did not criticise the "modernity" (the increasing secularisation and spread of Enlightenment trends), but exhibited a sort of sentiment for the "world going away" and a scientific interest in the cultural peculiarities of "Jewish antiquity". The author regretted often that "the Jewish people do not have its own ethnographer" who could save the fading culture as a "monument". He wrote in a letter to Chaim Żytłowski on the necessity of taking up the effort of researching the Jewish culture. He argued that only in reference to their own history and tradition Jews can survive in the changing world. All attempts at assimilation, vividly described by An–ski as "sewing onto oneself the heads and hearts of others" are doomed to fail. An–ski strived to start this identity project with gathering the Jewish folklore. He stressed that he will be happy if the Jewish Society for History and Ethnography will confer to him the execution of this task. He was quite alone in his interest in folklore, as St. Petersburg intellectuals of the time were rather critical of any attempts at referring to the tradition, advocating breaking away from it instead, in accordance with the progressive ideas popular at the time. An–ski thought, however, that ethnographic research will make it possible to reach the authentic sources of the Jewish nation's culture.

The main goals of the expedition were:

1. Gathering folkloric materials – tales, legends, fables, parables, songs, idioms, sayings, proverbs, riddles, peculiarities of local dialects, customs, beliefs, healing practices etc.

2. Gathering historical materials regarding selected townships – pinkas, old documents, memories and witness stories.

3. Gathering the items of Jewish heritage for the future Jewish museum: books, manuscripts, items of Jewish art including objects of cult, old clothes etc.

4. Taking photos of "human types", historical places, extraordinary buildings and items etc.

Gathering of the folklore was not supposed to be, according to An-ski, just a documentation of the representative examples of traditional tales or songs. He did not want to create a model of a shtetl. Instead he wanted to preserve the diversity of Jewish culture, document each observed variable of folk creations. His action was akin to creating an encyclopedia of Jewish life on the Pale of Settlement. It was most visible in the direction prepared by the ethnographer regarding material gathering – the "Jewish Ethnographic Program". An–ski wanted to create a complete set of questions, the answers to which would allow to describe the entirety of beliefs regarding the private and social life of a person. He planned the questionnaire to include 10.000 questions and be ready three months before the expedition. The first volume was to be published as late as 1914, however. It was entitled "Human" and consisted of 2000 questions concerned with the cycle of life. In his memoires, Awrom Rechtman who assisted the expedition during its first season, recounted that he saw the rough draft of the second tome entitled Szabes un jontef (Sabbath and festival), which was never to be published. Manuscript versions of two other unpublished questionnaires are kept in the National Library of Ukrainian State of Vernadsky. In 1913, An–ski published a short questionnaire entitled "Local historical program" focused on the history of specific communities.

It is worth noting that An–ski's fascination with Jewish heritage was almost religious. He wrote of folk works as an "oral Torah", which for many of his contemporaries might have been a risky comparison.

The first season of the expedition began on 1 July 1912 and the resources for its execution were assigned by baron W. G. Ginzburg.

Just before the start of the expedition anxious An–ski wrote to his friend:

"I am very nervous, as if facing a great unknown. How will it all unfold? Will I be able to gain trust of the poor and unenlightened, from whom I came myself, but from whom I also strayed so much over the years? It is terrifying at times. But at the same time I feel great joy in my soul, joy that the execution of my entire life's dearest dream is beginning" (after: Sergeeva I. „Etnograficheskie ekspeditsii…”).

Three seasons of the expedition brought a total of 70 visited tows, 700 Jewish heritage items of artistic and museum value gathered, around 1500 folk songs and 1000 folk, convivial, and synagogal motifs, hundreds of documents (diaries, manuscripts, pinkas, original drawings, ketubahs), 1500 photos of the interiors of old synagogues, grave monuments and objects of cult.

The description of places visited during the expedition can be found in the writings of J. Engel, A. Rechtman and the letters of S. An–ski to his family, friends and W. H. Ginzburg, the expedition's sponsor.

Journeys through Galicia and Bukowina on behalf of the Committee for Aid to Jews (1915)

During World War I, An–ski got engaged in activities aiding the Jewish population hurt by the war, simultaneously attempting to continue his ethnographic studies. In 1915 he made three journeys through Galicia and Bukowina on behalf of St. Petersburg Committee for Aid to Jews, aimed at helping the victims of war and pogroms. These experiences were described in drafts published under the title "Der judiszer churbn fun Pojłn, Galicje un Bukowina. Fun togbuch 1914–1917" ("The tragedy of Galicia Jews during World War I. Impressions and reflections from the journey through the country"). In addition to helping the refugees, organising evacuations, care posts, and canteens during the journey, An–ski also tried to save as many as possible of the Jewish heritage artefacts which survived the war. A symbolic finding from this period was a fragment of a parchment with Ten Commandments, found in the ruins of a synagogue. It was split in two so that one part contained "nie" [thou shall not], while the other phrases like: "kill", "steal" etc.

After the victory of Bolsheviks, An–ski left Russia and settled down in Vilnius. In 1919 he founded the Jewish Society for History and Ethnography. In Vilnius An-ski's best known work, entitled "The Dybbuk or Between Two Worlds", appeared for the first time. As the original script of the play in Yiddish had been lost, the published text was its second version, based on the Hebrew one, translated from the original by Ch. N. Bialik.

An–ski died on 8 November 1920 in Otwock. His body of work, published in Israel, contains 15 volumes.

The route includes 7 townships in Volhynia: Luboml – Volodymyr-Volynsky – Kovel – Lutsk – Ostroh – Dubno – Kremenets – Korets.

The route: 420 km, time of car journey – one week.

Visiting the townships along the route is connected to the topics present in the source materials (reports and folklore) and the preserved iconographic materials.

Luboml

We shall begin our sightseeing with a place called Luboml. It is hard to specify when exactly the expedition visited the town, but from the sources it is known that the shtetl was on the expeditions route, probably because of the Renaissance synagogue from the 16th century and numerous shtiebels. As reminisced by Yisroel Garmi in the memorial book of Luboml Jews published in New Jersey in 1997, An–ski visited Luboml accompanied by a journalist and photographer Alter Kacyzne in 1911. According to that account, An–ski and Kacyzne gathered the oldest men from the town in a shtiebel of Radzyń Hassids (Radziner Chasidim) and with glasses of vodka, hot tea, and groats cookies (retshene kiszelech) spent long hours at a table, wrote down many stories and legends about the past. According to the author of the memories, many motifs in The Dybbuk come from the notes made by An–ski during his visit to Luboml. The words from a play regarding the "sacred grave" can serve as an example. "When cruel Chameluk, may his name be erased, invaded the town with his Cossacks and slew half the Jews, he also murdered a young couple about to be wed. They were buried where they were slain. Both in the same grave. Since then the grave had been called a sacred grave... silently, as if in secret and every time when rabbi gives marriage, sighs are heard from the grave..." In The Dybbuk the couple is buried in a single barrow and their grave is visited by newly-wed couples, which dance around it with their guests to make the buried engaged couple happy.

Getting in touch with the locals usually looked the same during the expedition. Abraham Rechtman, in his memoires published in 1957 in Buenos Aires, describes the meetings of An–ski with Jews from the townships visited by the expedition. They usually began soon after the prayer in the synagogue. Initially the ethnographer was asked questions about life in the capital, but once the conversation was already well established he was gladly invited to homes, where the eldest, with a cup of coffee or a glass of vodka, shared their memories or recounted local tales. Rechtman also recalls old men who every evening filled An–ski's hotel room. Steadily boiling samovar, warm atmosphere and hospitality made conversations easy, and quickly songs and legends could be heard in the room. The success of the expedition, the volume of materials gathered resulted largely, according to A. Rechtman, from the locals' attitude to An–ski: "Both young and old spent days and evenings in his room. Only thanks to their love for him we managed to gather all that we did"

(A. Rechtman, "Yidishe eṭnografie un folḳlor: zikhroynes̀ vegn der eṭnografisher eḳspeditsie", 1957, after: Tracing Ansky...).

Not always, however, did An–ski and his companions manage to gain the approval of locals and write down interesting stories. In the report from the expedition written by Joel Engel, tasked with gathering musical folklore during the first season, we can find the details of problems encountered by the expedition in the town of Rużyn not distant from Luboml. "For some time they had us for grafomonszczycy, people trading in songs and fables. But An–ski with his august appearance, observance of rituals, and ability to talk to the elderly, here, as in other circumstances, could direct the situation suitably. It was hard to say the same about me. Aside from the fact that my Jewish was bad, I induced distrust from the elderly with just my appearance – a shaved face. But thanks to An–ski I could gain what I needed" (after: Sergeeva I. „Etnograficheskie ekspeditsii…”).

Very often groups of children surrounded the expedition's members, they eagerly shared their counting–out games and songs in exchange for kopecks. Sadly, when the children found out that for every new song they get five kopecks they started to create them themselves and distressed parents intervened with An–ski because children were escaping from cheder to spend time with folklorists.

The researchers also found out that the phonograph caught locals' great interest. When Engel took it to the streets very quickly a crowd gathered around him and wouldn't let him move. It once happened that when he was going out to a recording he asked Solomon Judowin, responsible for photographic documentation, to distract the locals by taking his camera. The method worked – the crowd moved toward the camera and Engel could secretly leave through the courtyard with his phonograph.

During the expedition An–ski tried not only to write down what can be presented as a folk creation, for instance a song or a counting-out game, but also what serves an important social and spiritual role, for instance folk chants, the healing power of which was still believed in, not dismissed as outdated or as superstitions. Folk texts which still had practical cultural meaning were hard to write down. An–ski applied a variety of strategies towards the town's residents, aimed at "mining" interesting spells out of them. In Abraham Rechtman's book we can read about what it looked like. "In almost every shtetl in Ukraine there were old women, to whom people would come for advice in difficult situations... these women practised magic with knives, socks, and combs; poured wax and used boiled eggs, they also knew hundreds of ways to cure their patient... we took the following strategies to get their spells from them. Sometimes one of us pretended to be ill, laid down in bed and we called the healer... During the healing one of us sat in a corner and wrote down all he heard, while the photographer took photos. An–ski frequently went to one such healer and complained about his perpetual bad luck, said he used to be a rich man once, a merchant, but now, sadly, he is poor, and going through a hard time in life having no income. After such explanation of his arrival, An–ski asked the healer for some magic spells which would allow him to find a way to stay alive. An–ski always stressed that he doesn't need alms, but he is willing to pay for the favour. The breaking of his voice and a story told in a simple manner almost always gave the desired effect. The old woman would fall for the story and start to feel sorry for the client, also hoping for profit. After discussing the price, the woman revealed her secret spell, while An–ski wrote it down (A. Rechtman, „Yidishe eṭnografie un folḳlor: zikhroynes̀ vegn der eṭnografisher eḳspeditsie”, 1957, after: N. Deutsch, "Jewish Dark..."). Once, however, it happened that the chanter, asked by the ethnographer to repeat her spell, got annoyed and told him that if we wants medicine he should go to the pharmacy.

Nowadays in Luboml there are barely any monuments of Jewish culture.

Volodymyr-Volynsky

An–ski's expedition visited Volodymyr in July 1913, during the second tour. The author's literary work is linked to Volodymyr by Chana Rochel Werbermacher, whose history had first been written down in 1909 by S. A. Horodetzky in his periodical "Evreiskaia Starina". Chana, a daughter of a rich merchant Monesz Werbermacher, was born in Volodymyr in the early 19th century. She was very talented and since childhood took interest in the studies of holy scriptures, to which men were devoted. Her fate, however, was to be married. The time preceding the marriage regrettably turned out to be very hard for Chana. Not allowed, according to tradition, to see the bridegroom before the wedding, she fell into despair. Her tragedy was deepened by the death of her mother and Chana spent days crying at her grave. One day, exhausted by crying she fell asleep on the cemetery. When she woke up in the night, she started to run screaming until she fell down and lost consciousness. The cemetery custodian carried her body to her father, who, seeing that after several weeks his daughter had not regained health, called various doctors and healers (Baal Shems), but none could help her. One day the girl woke up by herself – sat up on the bed and said she experienced a vision from god. According to her she was in heaven, where heavenly court gave her a new, elevated soul. Since that time she started to teach. She refused to get married, devoting her life to the study of Torah and Talmud. She was also given the power to perform miracles. People started to call her a Maiden of Ludmir (Ludmirer Mojd in Yiddish). There were also those who thought she had been possessed by the dybbuk and asked Mordechaj Twerski, a magid from Chernobyl to come to Volodymyr and banish the demon out of the girl. After looking at Chana he decided that there is a soul of an unknown tzadik in her, unable to find peace in the woman's body. Chana Rochel assumed men's roles: she behaved like a man, and a tzadik to boot – she prayed in a tallit and tefillin, took in pilgrims and the kvitlech, granted benedictions, sat at the honorary place during the gatherings at the table (in Yiddish called tisz) interpreting Torah and sharing sziraim (the leftovers she left after the meal). Inheriting her father's estate she bought a Beth Midrash with a special room in which she prayed and studied.

Her growing reputation and taking up the activities traditionally attributed only to men could not remain without reaction from other spiritual leaders from the Hassidic circles. They started to put pressure on Chana to stop her activities and marry, fulfilling the role designed for a woman in a traditional community. For some time Maiden of Ludmir abandoned her activity as a leader and teacher. She even married, but reportedly the marriage did not last long. Late in her life she travelled to Palestine and settled down in Jerusalem. In her footsteps came a small group of followers, with whom she prayed monthly in Rosz Chodesz at the grave of Rachel. She was buried on the Mount of Olives.

Lea, the protagonist from The Dybbuk also visits her mother's grave before getting married and also loses her consciousness. Her odd behaviour following the event is evidence to the fact that she is possessed by the dybbuk. Similarities between the history of Maiden of Ludmir and An–ski's play indicate that the author was most likely inspired by Chana Rochel's story. An–ski, fascinated by Jewish folklore, wrote down stories during his expedition and probably during his visit to Volodymyr he learned in detail the legend of the Maiden of Ludmir. According to Mosze Szejnbaum, the author of Pinkas Ludmir, An–ski heard Chana Rochel's story from Josele Dreyer leading the Chewra Kadisza brotherhood in Volodymyr (after: Deutsch N., An-sky and the Ethnography...).

It is additionally worth mentioning that Chana Rochel Werbermacher's history was also an inspiration for Isaac Bashevis Singer 's novel Shosha.

An–ski was in Volodymyr-Volynsky also during the aid mission during World Was I. In his writings from the time he notes that soon after he came to Volodymyr he called a council of several of the town's activists to think on the situation in town and the threat of deportation. During the meeting attended by around 20 people, it turned out that the residents are more afraid of evacuation than deportation, and are optimistic about the arrival of Germans. An–ski told everyone about what happened in most of the towns which went from the hands of one army to the other's. He stressed that in Volodymyr a cannonade and the town's destruction is very likely, especially fires being set and pogroms organised by retreating armies. Despite the warnings, the residents decided that fires or pogrom would not affect the entire town, so it makes no sense for everyone to abandon it. An–ski offered to create an Aid Committee, which in case of pogrom or deportation would provide supplies and prepare carts. "They replied that it is difficult to found such a committee. If everyone is banished then everyone will have to fend for themselves and will have no time for public affairs. I told them that such attitude to public affairs is unacceptable, even outrageous. It made an impression on them. Seven or eight people agreed to take this mission upon themselves" (An–ski S. "The Tragedy..."). After the founding of the Committee and preparing the plan of action it was decided that around 800 roubles can be gathered from across town. An–ski promised to provide a further thousand roubles. It was decided to buy several hundred poods of flour and purchase horses ahead of time. When the order to deport all residents finally came, they began to bake bread from the purchased flour. The situation in Volodymyr was hard at the time also because of the spreading cholera and typhoid. An–ski organised help of additional doctors who helped the residents, and suggested to the community's supervisor to escrow the most valuable items from the synagogue to him. It turned out, however, that all valuables, including old brass candelabra were in the keeping of the synagogue's custodian. The residents feared him, believing he works for the secret police, so without hesitation they gave him the valuable objects.

During the next mission in Volodymyr, An–ski intervened with the circuit chief in order to facilitate the residents' evacuation. At that time in Volodymyr there were many refugees from nearby lands. An–ski gave the local Committee 400 roubles to help people requiring it the most. The author personally witnessed bad treatment of Jews in Volodymyr. He noticed, for instance, how a Cossack guarding the door to the circuit chief office pushed an older Jew away from it. In reaction, An–ski shouted down the aggressive man and threatened him with legal suit.

On that day in a Volodymyrian coffee shop An–ski saw a young officer who told him than in Sokal, where he was with a sapper unit they blew up a train station, barracks, and several other buildings.

" 'But to have some fun too I also blew up a synagogue. Ha, ha, ha!'

'And why did you do that?'

' Why wouldn't I?'

'It is a temple!'

'A temple? What temple?'

'What is the prayer you say every day? <<In the name of the Father, Son and Holy Ghost>>. And the synagogue is the temple of the "Father". How could you desecrate a temple just to have some fun?'

He was a little disconcerted.

'I didn't mean I did it for fun. I was ordered to blow up the synagogue.'

'Wait.' I interrupted him. 'Did you use a lot of explosives to blow the synagogue up?'

'No, just some, it was a simple building!'

'I saw the synagogue. It's walls are an ell thick, it looks like a fortress, so how is it possible that you used so little of the explosives?'

'You are wrong. It was a wooden building. Only the foundations were made of stone.'

Whether he in fact blew up just a prayer house and lied about having done it "for fun" – I do not know.

Leaving the coffee shop I met a group of injured people. I stopped one of them and asked:

'Where are you coming from?'

'From Sokal' 'What is going on there?'

'Not much, it's calm. The Cossacks came back and broke into Jewish shops, stealing flour' ".

The building of a former Talmud Torah school in Volodymyr was preserved from the 19th century. The synagogue and the Jewish cemetery do not exist any more, but later on in the area of the burial of tzadik Szlomo Halewi Gotlib's (from Karlin-Stolin Hassidic dynasty) an ohel was built.

Kovel

The next place along the route is Kovel – it was there that the expedition went after their visit to Volodymyr. We also know that during the stay in Kovel the photographer Solomon Judowin visited a Talmud Torah. To this day a photo is preserved of children from Kovel standing in a circle.

The next place along the route is Kovel – it was there that the expedition went after their visit to Volodymyr. We also know that during the stay in Kovel the photographer Solomon Judowin visited a Talmud Torah. To this day a photo is preserved of children from Kovel standing in a circle.

During World War, I An–ski came to Kovel in the time of bombing runs. At that time he aided financially a representative of local aid committee, doctor Feinstein. It was her who told him that soon before his arrival three carriages transporting Jews banished from Luboml passed through here. 'Many refugees take carts or go on foot. There are such among them who fear going by train, as there is a rumour that along the way Jews are thrown out to the fields. In the township of Hołoby there were over a thousand refugees and Kovel committee started organising help for them" (An–ski, "The Tragedy..."). She also mentioned that in shops food is requisitioned, there is not enough bread and sugar. According to her relation, when the circuit chief was addressed to have him help acquire sugar he reportedly replied that "Jews can drink tea with salt". Due to the fact that Kovel became a transit point for the refugee movement, An–ski left a thousand roubles to Feinstein.

Today in Kovel, on the corner of Wołodymyrska and Niezależności streets one can still see the remains of the synagogue building, which is currently used as one of the halls of a clothes factory.

Lutsk

From Kovel we travel to Lutsk, with which the history of antiques belonging to the Jewish community is connected. They were conveyed to the Museum in St. Petersburg, as the local community wanted to save them from theft and wartime destruction. In 1915, the community of Lutsk gave An–ski a large chest with valuable antiques from an old Lutsk synagogue: a manuscript from the 18th century, two silver chandeliers with engraved images from the break of the 16th and 17th century, silver jugs of the Levites, a myrtle branch, a yad (a pointer for reading the Torah), a tas (a shield ornament of Torah), two hoods for the Torah, and a table cloth embroidered with a gold thread – items of total worth between 20 and 30 thousand roubles. An–ski transported these items to St. Petersburg. When in 1918 the museum was taken over by the Soviet government, the ethnographer conveyed the chest to the currently non-existent Museum of Alexander III.

The expedition visited Lutsk twice – here its first lap ended in 1914.

To this day in Lutsk there remains an 18th century synagogue building of defensive character. Currently a sports school is located there.

Ostroh

The next stop on the route tracing An–ski's footsteps is Ostroh. The expedition visited it twice, but it is worth mentioning also in the context of the manuscript – Sefer haCheszek [The Book of Desires] – found by An–ski during the journey. It is a book on a healer (baal shem) named Hillel, a known Kabbalist, and between 1732–1740 he was involved in, among others, banishing evil ghosts in the townships in Volhynia and Podolia. Sefer haCheszek is a collection of advices from the folk medicine, first of all prayers meant to serve the exorcisms. What is interesting, there are not only the examples of successful rituals, but also the cases when the dybbuk could not be banished from a person. Such a case occurred in Ostroh and Hillel describes it as follows:

"Once with God's help I encountered a terrifying incident in Ostroh in the Volhynia region. A pagan demon possessed the soul of a woman from that town. I was unable to attempt the ritual for several days. I sought aid from the great oaths in the synagogue – at the Torah scroll and in the presence of pious inhabitants. But the spirit answered me from the inside of the woman's body (may God deliver us): 'You are the rabbi who for six days tried to banish me, swore oaths over me and exorcised me using holy names. But you are unable to do me harm, weakened though are the evil forces enveloping my soul, weakening my limbs, sinews, and bones. This is not the place to give you the right to use holy names, as this is a place of filth located by the sacred synagogue. So if you wish to finish your work you must go with me and try elsewhere. Only near the seven scrolls of Torah and seven boys without sin, or seven (or more) just men will you be able to finish the ritual. This same day they speak their oaths let them follow you to the mikveh, pray with you and only then, with G-d's aid you shall succeed and I shall leave the woman's body. I cannot tell you just one thing – whether I leave her body with her soul or without it". (after: Petrovsky–Shtern Y., ‘We Are Too Late’...).

According to Yonathan Petrovsky–Shtern, the story can be seen as the manifestation of the spiritual crisis of the Hassidic movement (the dybbuk is stronger than the rabbi–exorcist), a motif apparent also in An–ski's The Dybbuk.

To this day in Ostroh one can visit the ruins of a synagogue and a renovated Jewish cemetery.

Dubno

The second season of the expedition began here on 17 June 1913. Abraham Rechtman, present during the departure, recalls in his memoires a local legend noted then by An–ski. It speaks of a Jewish merchant from Breslau who often visited Dubno, conducting business with count Lubomirski. Once the merchant came to conclusion that instead of travelling back and forth it will be smarter to settle in Dubno. He built a beautiful house in the centre of the city, brought his wife and became a member of the local community. As he felt obliged to local Jews and spent much time in the Beth Midrash house, he exhibited charity giving numerous donations to the needs of the students of that house of learning.

The second season of the expedition began here on 17 June 1913. Abraham Rechtman, present during the departure, recalls in his memoires a local legend noted then by An–ski. It speaks of a Jewish merchant from Breslau who often visited Dubno, conducting business with count Lubomirski. Once the merchant came to conclusion that instead of travelling back and forth it will be smarter to settle in Dubno. He built a beautiful house in the centre of the city, brought his wife and became a member of the local community. As he felt obliged to local Jews and spent much time in the Beth Midrash house, he exhibited charity giving numerous donations to the needs of the students of that house of learning.

The old Beth Midrash in Dubno was in a very bad state, however – walls full of holes could barely support the roof. Having no children of his own he could dote on, he decided to build a new Beth Midrash, which was to serve the community for years to come. He spared no resource, buying the best wood, bricks and hiring magnificent craftsmen. He brought candelabra from Germany and bought massive brass menorahs. For the opening he threw a great celebration.

When the festivities ended, the man came to Jews praying in the old Beth Midrash and gave them the keys, saying: 'These are the keys to your new Beth Midrash. Come and study the Torah with joy. I desire to serve you'. But the students looked around and said: 'We cannot accept your gift in our hearts. We cannot abandon our building like that. The walls and ceiling are pierced by our voices and long will cry after us. So until these old walls do not fall we should stay here'. Ashamed and broken, the wealthy Jew left. He and his wife were disconsolate. They cried bitter tears seeing the new Beth Midrash empty in the day and dark in the night.

Several weeks have passed, and a deep sadness made the wealthy man thinner, withered – he looked as if the entire weight of the world rested upon his shoulders. At that time the count called him. When he saw the state the man was in, he asked about what had happened. The wealthy man could not restrain his grief and burst intro tears telling the count the entire story. He listened and said nothing. But on the coming Friday, just before the Sabbath when Jews went to perform a ritual oblation, farmers armed with axes and iron chains provided by the count appeared at the old Beth Midrash. They knocked the building down and transported the Aron Kodesh, a scroll of Torah, and sacred books to the new building built by the wealthy man. When Jews returned from the mikveh and saw what had happened they came to the conclusion that the wealthy man simply wants to force them to move to the new house of learning. So they turned their backs on him and went to other prayer houses in Dubno to study the Torah. When the wealthy man saw what the count had done, his despair became even greater. He tried to convince people that this damnable deed had been done without his knowledge. He begged the rabbi to show mercy and help him clean his name.

On that evening, when the Sabbath had ended, the rabbi called a meeting and told the scholars from the old Beth Midrash to attend it. The wealthy man addressed the community and repeated under oath that he had nothing to do with the committed outrage and that the count did it of his own account. He asked the students not to be stubborn and come pray in his new Beth Midrash. Obedient to the rabbi's prompting, they finally decided to follow his advice and started to pray in the new place – to the great joy of the wealthy man and his wife. The man had his place in the prayer house, near the door among the poor. For the rest of his life he humbly assisted the scholars. Everv since that time, the building had been called Breslauer Kloiz.

During an aid mission in 1915 An–ski, noted a story told to him by some Jew from Dubno who found himself in Radziwiłłów during the pogrom organised by the Cossacks. "Cossacks were raging in the streets, breaking doors and windows, robbing. Jews closed themselves in houses. He knocked on several doors, but nobody wanted to open the door for him so he had to sleep in the street. Suddenly he saw a running Jew. When he saw the newcomer from Dubno, he ran up to him and asked: 'Come with me and save me!' Of course he went with him and it turned out that on that day came the date of praying for a member of the family who passed away and they lacked one person necessary for the minyan prayer. After saying the evening prayers the host led the guest to the street in order to bless the new moon (kidusz lewana – a customary thanksgiving prayer for the arrival of a new moon, said soon after the start of a new month).

'How?! There is a pogrom raging outside' the newcomer was stunned.

'But look at how beautiful the moon is! The pogrom will rage tomorrow too, but we may not see the moon then any more'

Both went to the street, Cossacks raging around, while they blessed the moon" (An–ski S. "The Tragedy...").

To this day in Dubno an 18th century Great Synagogue building is preserved, at the Cyryla i Metodego street, some residential buildings are preserved as well. In Dubno one can also visit the Jewish cemetery, where around a dozen gravestones remain.

Kremenets

An–ski's expedition visited Kremenets during the first two seasons (i.e. 1912 and 1913). We know the course of the July 1912 visit quite well thanks to the Memorial Book of Kremenets.

An–ski's expedition visited Kremenets during the first two seasons (i.e. 1912 and 1913). We know the course of the July 1912 visit quite well thanks to the Memorial Book of Kremenets.

The report's author recounts that An–ski came to Kremenets with Zausman Kiselgof (a scholar of folklore and musicologist) and Solomon Judowin (painter and photographer). It was on a Friday, the guests stayed at the hotel of Mosze Melamed, who was clearly surprised by the guests who came from St. Petersburg and spoke Yiddish. "Some weird Jews came and while registering they said they came from St. Petersburg" – so he told in town about the newcomers. An–ski and his companions were interested in the life of Kremenets Jews, with curiosity watching their lives through a window. In the memorial book we can read:

"Usually, Friday nights saw streets full of young people. This time, however, they all stood at the hotel staring at a window. They envied the inner circle which had easy access to the hotel. At that time barber Sender Rosenthal and Jasze Rojtman, baker Szlojme's son, approached the selected group. Both waited at the hotel because they learned that An–ski had a deal with the owner that he will be taken to a small Hassidic prayer house for a Sabbath morning prayer and that the owner went to the blind Pejsa, the szames (custodian) and told him a guest will be coming. An–ski asked about the Hassidic traditions in the house of learning and the details of Hassidic behaviours. He was especially intrigued by the harmony between Hassids, by the fact that all gathered there and prayed the same way, except Radziner, who had their own synagogue. Saying goodbye to his companions from the expedition An–ski said: "have a good Sabbath" indicating thus to his colleagues that they should behave in a respectable manner, not speak Russian, in short behave "Jewish".

During his stay in Kremenets the crew led by An–ski managed to record unique Hassidic niguns, folk songs, write down a lot of local stories and gain two brass lanterns from the great synagogue for the St. Petersburg museum.

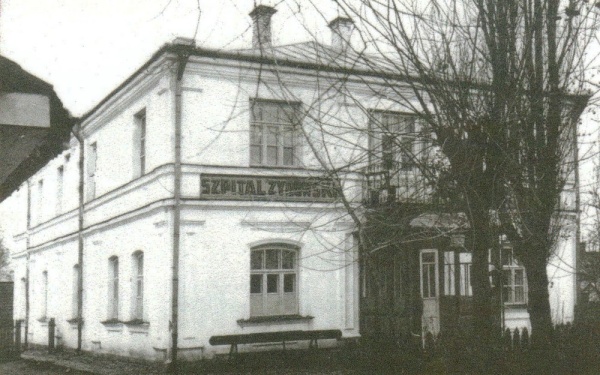

The synagogue building exists to this day – currently redesigned to be a bus station. The Jewish cemetery is also preserved.

Korets

An–ski's stay in Korets is commemorated to this day by a collection of photos of coach-men and blacksmiths.

An–ski applied varied strategies to convince the residents to allow him to take photos of them and to have them share their knowledge. When it did not work he used a trick – yes, the way it happened in the case of cheating the healers. It was harder for him to explain to the residents the purpose of gathering handicrafts and other souvenirs. To the residents of the shtetl the idea of a folk art and a Jewish secular museum was not very understandable nor convincing, especially given the fact that in the early 20th century there was still a dominant colonial paradigm of collecting functioning in museums. What is worse, An–ski gathered not only the elements of the synagogue furnishings, documents, and books, but also objects, which would never be touched by a pious Jew, for instance a skull dating back of Khmelnytsky's uprising, or a finger cut off from a boy by a family wishing to save him from being drafted to the army. Human remains used to be exhibited in museums of the time, but it was unacceptable for a religious Jewish community. A man met by An–ski kept his finger to have it buried with the rest of his body, in accordance with tradition, and only a miracle allowed the ethnographer to convince him to sell it. The skull with marks of being damaged with a weapon An–ski dug up on the cemetery himself, and transported to St. Petersburg in secret, knowing it would shock the residents. It was because often his mere presence on a cemetery was undesirable – because his last name was Rapoport he was considered a kohen (a descendant of priests from the Jerusalem temple, who were prohibited from walking in cemeteries due to an obligation to keep the ritual purity).

Sometimes however the researchers also met problems with recording the religious works to the phonograph – the residents believed that there is power in the resounding melody, in an individual performance of a given prayer, or song – especially if they are sung with an honest intent (kawone). Jews from shtetls have heard of phonographs, they called them "edisons", but few understood their function. An–ski and his companions had to demonstrate each time how the device works. Usually it happened in the house of learning, after prayers. In order to present the phonograph, one person from the research crew sung a song purposefully laughing in the middle, and then played the sound from the tube. The listeners realised that the entire situation became immortalised. After such a demonstration everyone was amazed by the possibilities given by the phonograph and more than one wished to immortalise their singing. The fact that the recordings of religious pieces were still not treated equally to the live performance is evidenced by the reaction of Awrom Bloch, staying at the court of tzadik Moiszele Korostiszewer from Chernobyl dynasty. Asked to sing something, he told the story of reb Motele, who once told him to sing to the phonograph, "pouring his soul" to test his belief that the phonograph would not record a pure prayer, only such that stays on earth. He referred in this to Beszt himself, who taught that tainted prayers stay imprisoned in the walls of the prayer house without being elevated to the heavens. And such is – said Awrom Bloch – the secret of "edison" – it only catches simple phrases and tainted songs.

Paradoxically, however, An–ski was well received by the residents. They did not suspect that the expedition members were stealing the kvitlech from the graves of tzadiks, while the ethnographer himself eagerly (as he wrote in a letter to Żytłowski in 1914) would "replace Beszt's grave for a good Jewish Leonardo da Vinci" (after: Safran G., "Wandering Soul...").

To this days there are matzevahs preserved in the Jewish cemetery.

Prepared by Agata Maksimowska

Bibliography:

An-ski Sz., Dybuk. Między dwoma światami. Legenda dramatyczna w 4 aktach, tłum. M.Friedman, wyd. Teatr Rozmaitości, Warszawa 2003.

An-ski Sz., Tragedia Żydów galicyjskich w czasie I wojny światowej. Wrażenia i refleksje z podróży po kraju, Południowo-Wschodni Instytut Naukowy, Przemyśl 2010.

Deutsch N., The Maiden of Ludmir: A Jewish Holy Woman and Her World, 2003.

Deutsch N., An-sky and the Ethnography of Jewish Women w: Safran G., Zipperstein S. J. (eds.). The Worlds of S. An-sky: A Russian Jewish Intellectual at the Turn of the Century, 2006, pp. 266-280.

Deutsch N., A total Account. S. An-sky and the Jewish Ethnographic Program, “Pakn Treger. Magazine of the Jewish Book Center” nr 58, fall 2008, pp. 28-35.

Deutsch N., The Jewish Dark Continent: Life and Death in the Russian Pale of Settlement, 2011.

Encyklopedia YIVO

www.yivoencyclopedia.org, dostęp 15.06.2015.

Goldberg S. A., Paradigmatic Times: An-sky’s Two Worlds, w: Safran G., Zipperstein S. J. (eds.). The Worlds of S. An-sky: A Russian Jewish Intellectual at the Turn of the Century, 2006, pp. 44-52.

Kagan B., Luboml: The Memorial Book of a Vanished Shtetl, 1997.

Kantsedikas A. S., Sergeeva I., The Jewish Artistic Heritage Album by Semyon Ansky, 2001.

Petrovsky-Shtern Y. ‘We Are Too Late’: An-sky and the Paradigm of No Return, w: Safran G., Zipperstein S. J. (eds.). op.cit., pp. 83-102.

Photographing the Jewish Nation: Pictures from S. An-sky's Ethnographic Expeditions, Avrutin E. M., Dymshits V., Ivanov A., Lvov A., Murav H., Sokolova A. (eds.), 2009.

Roskies D. G., An-sky, Sholem Aleikhem, and the Master Narrative of Russian Jewry, w: Safran G., Zipperstein S. J. (eds.). op. cit., pp. 31-43.

Safran G., Wandering Soul. The Dybbuk's Creator, S. An-sky, 2010.

Sergeeva I., Etnograficheskie ekspedicii Semena An-skogo v dokumentakh, „Skhidnyi Svit” Nr 3, 2009

http://in-music.su/history/history_text48.php, dostęp 15.06.2015

The An-ski Expedition in Kremenets, Translated from the Yiddish By Wolf Krakowski and Paula Parsky Excerpted from Memorial Book of Krzemieniec (Ukraine) Edited by: Abraham Samuel Stein Published in Tel Aviv, 1954.

Tracing Ansky: Jewish Collections from the State Ethnographic Museum in St. Petersburg, Catalog of the Exhibition in Joods Historisch Museum, Amsterdam 1992.

![Kremenets, a house - headquarters of the Związek Kupców [Trader's Union] Kremenets, a house - headquarters of the Związek Kupców [Trader's Union]](/cache/dlibra/image/89/89964/600x1024/)